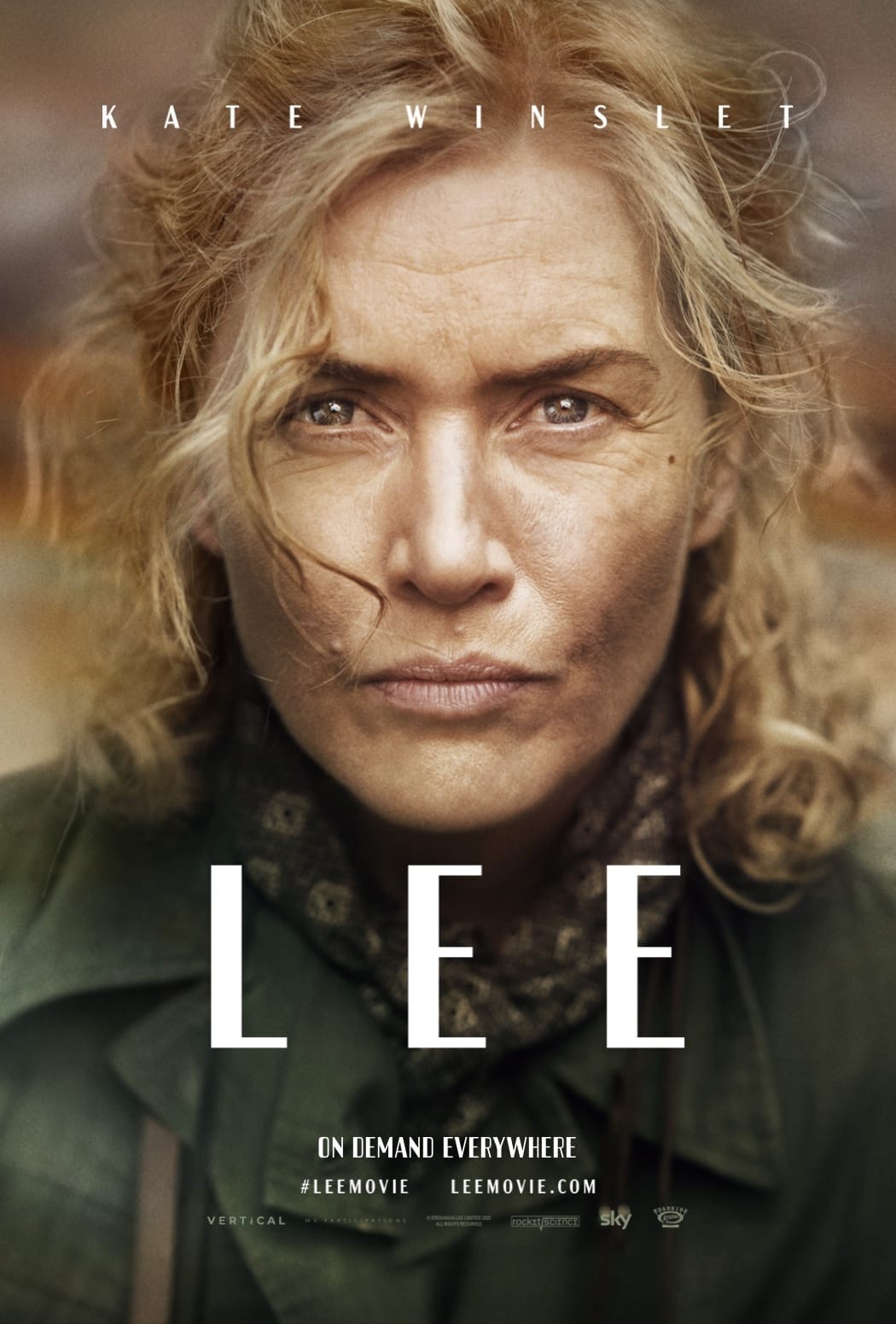

"Lee" Tells the Story of One Woman's Exception

"I'd rather take a picture, than be one." - Lee Miller, the titular character in Kate Winslet's award-nominating turn in a film worth watching.

The film Lee (2023) [Trailer] details the life of Lee Miller, a celebrated 20th-century female photographer, photojournalist, and war correspondent. Gruff and terse and generally seen with a cigarette dangling from the side of her mouth, Lee Miller was an exceptionally keen observer, bright, well-traveled, and multilingual, speaking French and English. A former fashion model, who summed up her modeling career legacy as “tits and ass,” Miller became a serious documentarian of human existence during and after WW2 with her renowned photos depicting the ugliness of war and its ravages (from the infirmed patients on the front line to the somber, yet hopeful liberation of Dachau), if not its absurd post-war realities (Allied officers having drinks and happy hour at Hitler’s home after he was declared dead).

The film’s premise follows a fictional conversation between Lee’s son, Anthony, played movingly by Josh O’Connor (La Chimera, Challengers), who in real life penned the book on which the movie is adapted, and Lee right before her passing in 1977. An interesting footnote is that Anthony never knew of his mother’s illustrious career as a wartime photojournalist for UK’s Vogue until after her death when he noticed a few of her photographs in the attic. One can thus imagine that writing a book detailing such a conversation would be a cathartic exploration for Anthony and afforded him some solace as he grappled with his mother’s multi-dimensional life, of which he knew only fragments.

“You’re making a big deal out of nothing. They’re just pictures.“ - Lee Miller to her son Anthony

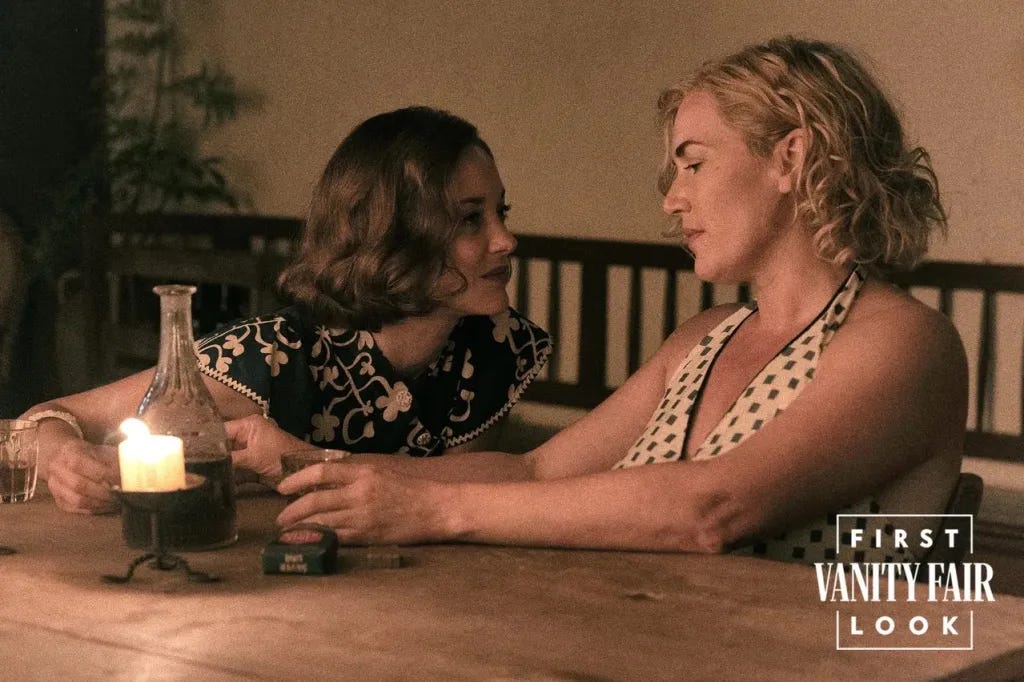

The first half is slow-burn. Starting with a flashback in 1938, it presents the joie de vivre of French bourgeois country home life, with fashion editors of the day and former models like Lee enjoying each other’s company. There, it’s commonplace for women to bathe at the dining table outdoors sans chemise, and accordingly, we see Winslet’s breasts a number of times on display. It’s in this milieu that Lee meets Roland Penrose (Alexander Skarsgård), a British upper-class Quaker who is an art historian, collector, and artist. Lee and Roland size each other up when they first meet, an instantaneous connection, equal parts distrust and admiration on display, which ultimately gives way to respect and love. One of the more beautiful aspects of their relationship, as it evolves, is that Lee doesn't want to be taken care of and she resists his pleas, but she loves him, and he loves her, and there’s a mutual acceptance.

The Myriad Manifestations of Male-Female Love

While Lee’s female friends all poke fun at her uncanny ability to seduce and charm the men in her life, her relationship with the central male figures in the film, both Roland and later, her “ride or die” wartime photographer peer, Dav(y) Scherman, a reporter for Life magazine, is far more complex and multi-faceted. The depth and diversity of love portrayed in this film, particularly in the context of relationships between men and women, is attributable to the female perspective at its helm. There's a nuanced emotional resonance throughout the work that seems to reflect a distinctly feminine sensibility. Ellen Kuras, who coincidentally was the cinematographer for Eternal Sunshine for the Spotless Mind, another Winslet film, is the director here.

Abuse, Power & Finding Purpose

One of the weaker structural elements of the film is following the through-line undercurrent of Lee’s fierce protectiveness of the vulnerable women and girls she encounters. At the midpoint of the film, there’s a subplot involving a French woman who is deemed “a collaborator” (une collaboratrice) and vilified and assaulted by male Allied officers. As Lee talks to her, she learns that the woman trusted a Nazi unknowingly and was deceived. Lee does her best to watch out for this woman, but unfortunately, there’s not much she can do. In another scene, an Allied soldier is attempting to rape a French girl in a seedy alley when Lee stops the altercation and threatens to chop off his balls (in fewer words), chasing him away and giving the girl her knife for the next time this happens.

“It happens all the time, and they just get away with it.”

After this, Lee proceeds to drink herself into a stupor, in a display of maladaptive, harmful behavior that escalates as the film goes on. All of this increased emotional vexing is explained away at the end of the film, in a scene that takes place at the UK Vogue office, as Lee comes out of a manic episode of fury and feral rage in response to her death camp photos being rejected by the magazine (they were eventually published in real life in the US Vogue in June 1945 in an article called “Believe It”) In particular; she’s upset at the lack of coverage of one of the Jewish girls she photographed, who was raped and brutalized at a death camp. In Lee’s defense, she is right, however heightened her reaction is. Hiding ugly truths and concealing them from the public doesn’t make them disappear. It often does more harm, ensuring people are less prepared for when something like this happens in the future, as Jews know well after the events of October 7th, 2023.

Regardless, we learn in Lee’s monologue her backstory - that she had been raped by a male adult friend as a young girl and sworn by her mother to secrecy. This has likely fueled her quest to protect women and girls and tell war stories, documenting the unseen and unheard voices in what often comes down to systemic abuse situations. I can buy all of this, but the admission part felt weak, like a quick wrap-up of a tawdry, difficult-to-share detail, likely because of the shame involved. It didn’t serve Lee’s story and felt inauthentic to her character.

Wartime Realities & Dissemination of Information

Is it, in fact, an ugly truth that mass media coverage favors stories that keep readers (or media sponsors) enthralled and controlled, like in an Orwellian universe? The film contends with this.

At one point, Lee is meeting with a friend of hers from pre-war times, after the liberation of Paris in August 1944, and her friend talks about people going missing and what’s happening to them. No one knows. Davey and Lee look at one another in consternation from across the decadent table they are sitting at in a fine Parisian establishment. When Lee calls her editor in London, she knows nothing about people going missing. By 1944, while instant wartime news transmission was not necessarily a regular occurrence, the fact that so little information about Jews, Romas, (and other “undesirables” deemed by Nazis) being rounded up and herded into cattle cars for the destination of work and then death camps, is astounding. As Lee and Davey come face to face with the horrors of the murdered (gassed) Jewish people in trucks, it’s like you’re watching a reveal of a whole new horror for the two of them. This is where the movie picks up and seems to find its footing a bit more.

As early as March 1942, reports of a Nazi plan to murder all the Jews – including details on methods, numbers, and locations – reached Allied and neutral leaders.[Link]

Interesting Real-Life Tidbits

This film was screened at 2024’s TIFF, where Anthony Penrose (Lee’s son) and his daughter (Lee’s granddaughter) discussed Lee Miller’s legacy. They spoke of her alcohol abuse in the subsequent decades post-war as a way to cope with the pain of past trauma. Penrose finally made amends with his mother in the years preceding her death.

Lee and Roland were influential in promoting Surrealism and International Modernism in Britain. They were friends with Picasso and he saw her as [his muse].

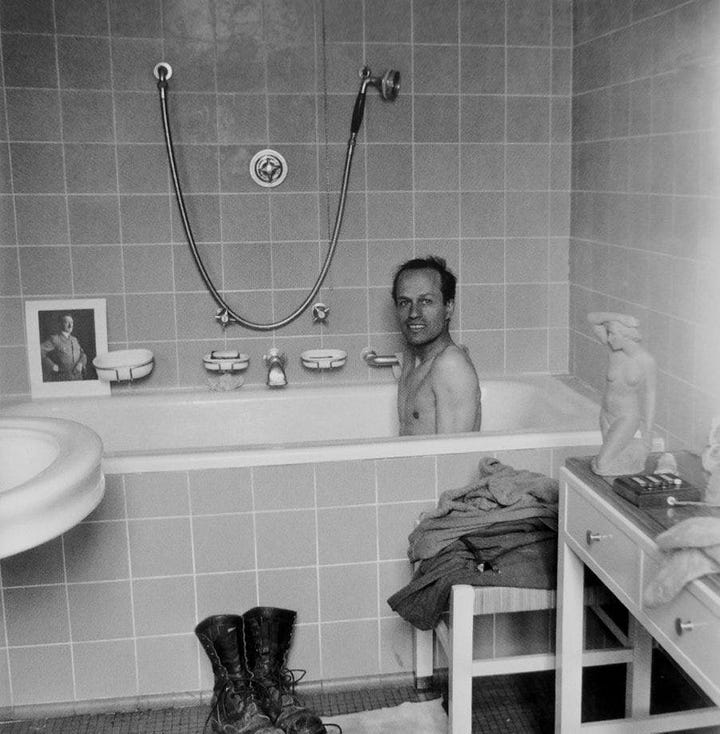

In the film, Lee and Davy gain entrance to Hitler’s apartment after he’s declared dead. As they enter, they bear witness to Allied officers in their undershirts with snifters playing music and victoriously walking through the apartment. Lee and Davy lock themselves in the bathroom and take these iconic photos. Visible here is the mud they tracked on the white bath mat with their boots, which was intentionally done.

Davy Scherman and Lee Miller in Hitler's Bathtub For more on Lee’s work and legacy, check out these links 🔗:

Believe It (US Vogue, June 1945)

Witness to the Fall of Concentration Camps (The National WW2 Museum - New Orleans)

Lee Miller: Women at War (The National WW2 Museum - New Orleans)

Lee Miller in Combat (The National WW2 Museum - New Orleans)

Lee-isms

This film has some great one-liners and dialogues:

There’s so much light in a person’s life, right up until the moment there isn’t.

All interviews are interrogations. The good ones, anyway.

Why can’t women go to the front line?

You’re making a big deal out of nothing. They’re just pictures.

Lee: Tell me about your mother.

Anthony: I spent my entire life thinking I was the problem, my mere existence. Took me a long time to realize it wasn’t me. It was her. I felt like she blamed me for everything that went wrong in her life and made me feel like I ruined everything for her. Do you have another explanation for it?

Lee: Well, that’s disappointing.

TIME IS RUNNING OUT TO CAST YOUR VOTE

Cast your vote for the top 2024 TV and film performances here

The big winners’ reveal will be on January 4th.

Twin Films - MUSIC Themed Fun

For January’s Film Chat, we’ll discuss “Twin Films,” which refer to films with the same or similar plots released at different studios at different times.

Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis (2022) on 1/12 and Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla (2023) on 1/19.

correction: The original post cited that the film was screened at 2023’s TIFF. It was 2024.

Excellent review of this film. About 15 minutes into the story Jeffrey and I almost turned it off. We felt it had a slow beginning.

I loved the detail of Lee’s personality as a protector of women. I know women were treated bitterly if they were a “collaborator.” It made me question, What would I do— if I was starving (and not Jewish) and a Nazi officer offered me food and shelter in exchange for sex. I probably would have joined the resistance and ate shoe leather. But it’s a good question to ask yourself.

Movies like this would be hard for me to watch, which is why I passed on it. I'd heard about it, of course, but it was a nope for me. But Lordty, props to the photojournalists that did this type of work. I can't imagine. This kind of reminds of me that movie "The Bang Bang Club", except it was about a group of four combat photographers capturing the final days of apartheid in South Africa. I ended up watching, like, the final 15-20 mins of it because of Taylor Kitsch (very under-the-radar actor). I wouldn't have been able to watch this one all the way through, either.