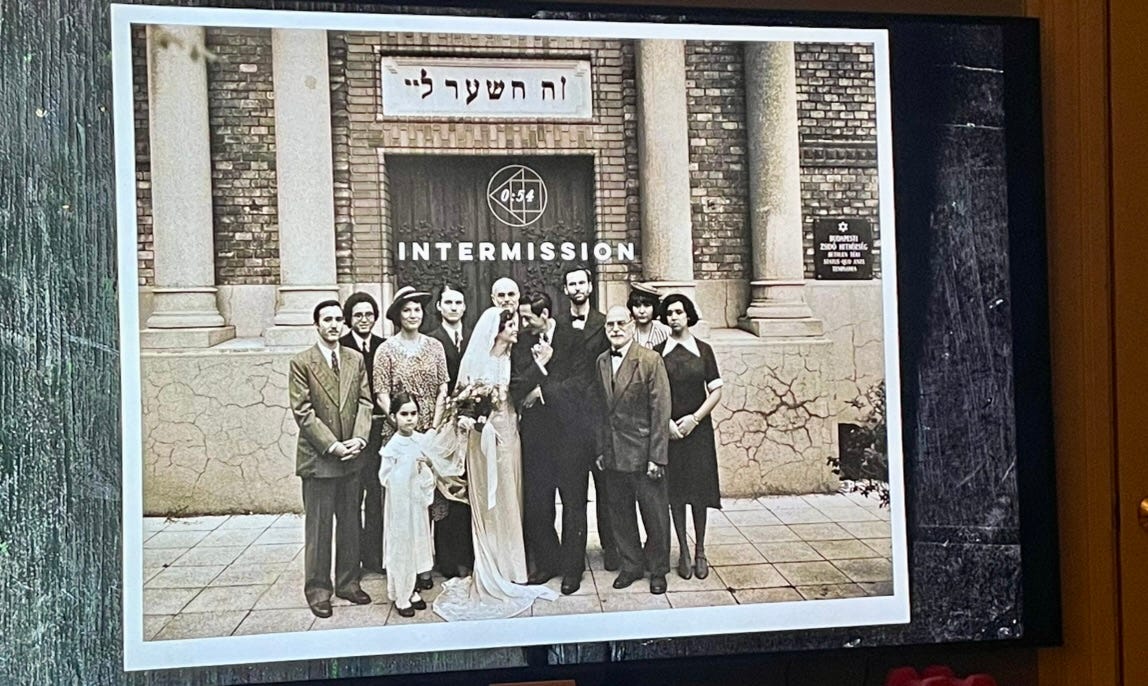

Premise: Hungarian-Jewish Holocaust survivor and Bauhaus-trained architect László Tóth (Adrien Brody) rebuilds his life in Pennsylvania starting from scratch. The film spans from 1947 to 1980.

Themes: Resilience, Holocaust, European Jewry, Trauma, Grief, Guilt, Parasitic Relationships, Abuse, Architecture (to a much lesser extent)

Background - A bit about me & why this film is personal

The Personal

The Brutalist [Trailer], up for 10 Oscar Nominations, including Best Film, Best Director, Best Actor, and Best Supporting Actress, is now streaming wherever you buy your favorite films. I chose Prime and paid $20 for it. Still, it's better than going to the theater for such a long sit-down. I could pause this film as much as I wanted whilst making my delicious omelet, replaying scenes of significance, and taking pics of the things that appealed to me.

Before I give my thoughts on the points being lodged against this film (from architecture enthusiasts who run amok at the “brutalist” classification to those camped on the side of how a younger Millenial non-Jew filmmaker non-Hungarian does justice to a tragedy as large and complex as the Holocaust, not to mention rooted in Jewish experience), I want to talk about my history because I think context is everything, when it comes to our viewing experience and the mark it leaves.

Ok, but first: This is where the film’s “surround sound” effect fails miserably, especially given the global stage it’s given to discuss the ill effects of anti-semitism and hate acts. Or even to discuss trauma, in more meaningful, universal ways. The film does this, the press circuit and awards speeches do NOT. Instead, it’s all down to one man rebuilding his life after a war. In this way both Brody and Corbet have let the story and the film down, stripping it of a soul, because WW2 was not just “a war” in our modern world - it was a crusade against the engineered annilhation of the Jewish people by people who sought to murder all of us. That trauma seeps into the gene pool (It’s called epigenetics). Have you seen A Real Pain? You really should.

Back to Me

The paternal side of my family is from Hungary. I have relatives who fought on the Austro-Hungarian side in WWI. My grandfather immigrated to NY as a young adult. My dad grew up speaking German but also knew Hungarian. He still gets a certain look in his eyes when he hears Hungarian, and, as an academic and a polyglot, he takes his dictionary out to make sure he’s translated the word correctly from whatever language he’s deciphering. Some of those dictionaries are heavy, too.

The newspaper clipping from my grandfather’s store in Budapest hangs in my dad’s hallway in a language that may as well be Greek to me - of course, this was all pre-WW2 stuff. Ashkenazi (European) Jewish history is still divided into life before and after the war, even if the war being referenced is nearly a century old. I worry that the dangers of overlooking the Holocaust will fade away along with my generation, thus erasing it entirely from history, and this is problematic for many reasons, which I will not get into too deeply here. Instead, I’ll talk a bit more about my Hungarian connection.

As a kid, I remember feeling exotic when I listened to Hungarian. Even names were more poetic. My name is Beth, and I am Erzsébet in Hungarian. Sofia is Szófia. Coincidentally, two of these names are characters in the film, too.

My grandfather was a business owner and very skilled with his hands, not unlike Attila, the furniture store owner and the character Alessandro Nivola plays, who changed his name from the Hungarian Molnár to the English variation, Miller. Attila Americanizes his business, changing it to “Miller & Sons,” and as his cousin, László, points out, “He is not a Miller, nor does he have any sons.” The memo is that coming to America requires more than physical and cultural adjustment; it’s reinvention.

My paternal grandmother’s family was also from Hungary, but further back. She was born in New York, around 100 years ago. Felicity Jones’s character, Erzsébet, László’s wife who joins him in America ten years later, in many ways, reminds me of her. In the scene at the end of the film where she stands up to industrialist villain Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) for his brutality in front of all his influential and wealthy peers during a family dinner, effectively shaming him, I could imagine my grandmother standing up for any of her family in this way. In fact, she did for me once, on a smaller scale, when all 5’0 and 110 lbs. of her went to confront middle school bullies who were making my Hebrew School life a living hell. To this day, I still hate Metallica because of the one kid who wore that band’s shirt all the time. I don’t think my life is any worse off for it, either. I was mortified at the time that my grandmother did this, but it’s the thing I hold onto this many years later - her ability to be relentlessly courageous in standing up for the people she loved, of which I was fortunate enough to be included. This demonstration of her love touches me in ways that are hard to express, but my heart aches that I didn’t get to know her better. She died when I was quite young.

The Immigrant Mindset, Trauma, and Coping Challenges

The one commonality to the immigrant experience, which I still carry the weight of, even a generation removed on my dad’s side, is the upholding of living responsibly and in accordance with those who have sacrificed to get me here. I don’t take that for granted, and I do believe my strong inner drive and discipline are connected to this. “At any point, it can all be taken away” is never far from my thoughts. As Jesse Eisenberg’s character incisively comments in A Real Pain, it’s the price that comes with being the “product of 1000 miracles.” Unfortunately, as that film also suggests, so is the dark side of seeking relief from pain with maladaptive coping.

In The Brutalist, László’s humbled and awe-inspired moment comes when he sees a profile on his career in a Hungarian magazine with proof of his buildings still standing in his homeland. His quiet tears encapsulate the weight of his experiences and the bittersweet nature of his success. Through his tears, he expresses grief about all that was lost in his former life as he takes stock of his current meager existence as a construction worker in his early days in Philly. The film explores how László copes with what he experienced while at Buchenwald Concentration Camp - his trauma - through substance abuse and using drugs as a form of escape. This struggle with addiction spans many years, illustrating the long-lasting impact of his wartime experiences.

To add to his trauma, once he finally gets a chance at success, when he’s commissioned to build a community center in Doylestown, PA, he is once more objectified and seen as less than because of his background. He’s fetishized through the evil Gatsby caricature and László’s benefactor, Van Buren, and his cronies because he’s looked upon as “exotic,” but he’s never accepted by them either, no matter that he’s a brilliant architect and a much more educated man than any of them. It always surprises me, even as an adult, how people judge others on the basis of an accent. Maybe this is also because, as a child, I was exposed to accents (mostly from Central and Eastern Europe) and romanticized the differences, though, like any kid, I valued not being different a whole lot more.

Controversial Topics & More

The Film Gaining OSCARS’ Momentum and its Problematic RADIO SILENCE on László’s Religious/Ethnic Identity - Michael Lewis raises a worthwhile argument in his assessment, which I summed up in the post below.

The film’s “Epilogue” suggests for the first time that László Tóth used architectural and psychological elements from his experience in the concentration camp in his designs for the Van Buren Institute/Community Center. In the course of the story, we learn he is passionate about the height of the ceilings, even paying out of pocket for this when the construction runs over budget. Additionally, he adds a tiny window pane at the top of each of the small rooms to indicate that, however claustrophobic and tight, the glass symbolizes freedom and hope. This was meant to mimic his experience in the camps. All of this stands in stark contrast to László’s answer earlier in the film to Van Buren about how he sees architecture effectively as something that defined by its shape- a cube is a cube is a cube, and there’s nothing more to it. Clearly, like most artists, he used architecture to express his inner life and the myriad of conflicting emotions.

On the topic of context…The use of Goethe’s quote in the opener and its persistent message of “none are more hopelessly enslaved than those who believe that they are free,” needs some explanation. The rest of this philosophical meaning is much more hopeful and self-determined, and in line with the statement made by Szófia, László’s niece, at the end, when she says that her uncle always instilled in her, “People will always tell you it’s the journey. It’s not. It’s the destination that counts,” which of course runs antithetical in nature to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ideology of “It's not the destination, it's the journey.” Hard work and the desire to treat each day anew make the difference.

Brutalist Architecture Debate - Is László’s work really representative of the “Brutalism” movement of architecture? The one characterized by a post-war concrete slab of ugly symmetry aesthetic that represented all that was wrong in the world? It looks close enough! The other complaint is that no one mentions the term, ‘Brutalism” itself in the film. Some quick research indicates there might be a reason for that. The term "brutalism" was first used around 1953 by British architects Alison and Peter Smithson to describe a design for a house in Soho, London, which they referred to as "the new brutalism"; however, the term gained widespread recognition when architectural critic Reyner Banham used it in his 1955 essay "The New Brutalism" to describe the emerging architectural style. It would have been very new to the U.S. at the time that László started experimenting and building The Van Buren Institute, so this might explain why. Louis Kahn was one of the most prominent Brutalist architects of his day. His bathhouse, which was part of the Trenton, NJ Jewish Community Center, was long seen as the pinnacle of Brutalist architecture. [Learn more here]

The opening credits deserve an award for innovation in style and execution. I loved that the camera kept rolling with the scene of the back of the bus moving from NY to PA. It was incredible. The credits were there and highly stylized for effect but in motion along with the moving vehicle. I also truly enjoyed the chapters.

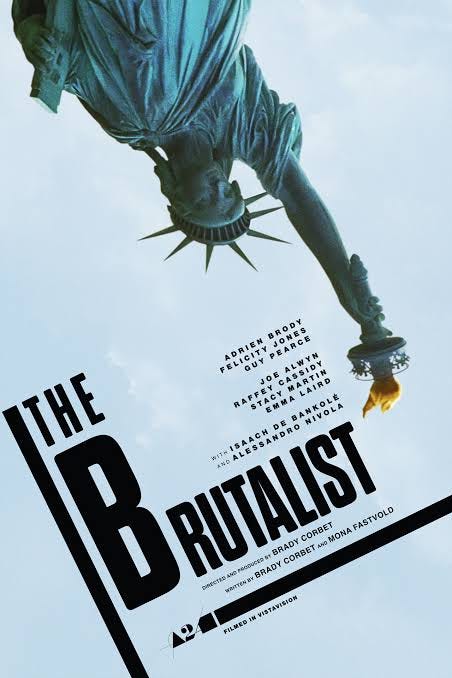

The intro to Ellis Island with the upside-down Statue of Liberty is probably one of the more memorable film intros I’ve seen artistically. Corbet clearly knows his visual cinematography, which makes for iconic moments like the one in the movie poster.

László Tóth is not a real person. Well, scratch that; he was a real person and one who allegedly achieved worldwide notoriety when he vandalized Michelangelo's Pietà statue on 21 May 1972, but he’s not the real-life inspiration for The Brutalist’s Tóth. More so, Brody’s character is meant as a composite of Jewish Hungarian architects at the time, like Paul Rudolph, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, László Moholy-Nagy, Marcel Breuer, and Ernő Goldfinger.

Favorite Couples’ Dialogue

Erzsébet is newly reunited with László and trying to be intimate with him. She feels rejected, and he feels frustrated. She is now confined to a wheelchair due to malnutrition during the war.

Erzsébet: I’m worried I look old. That you don’t find me attractive anymore.

László: We are both no longer young.

Erzsébet: That’s unkind. Say something kind.

László: I love you, you cow!

Final Verdict

I quite liked the film, but again, it’s personal or subjective, as we like to say. I could have done without the rape scene which catapulted an already long film into a very, very, very long film. It also distracted me in the final 1/5th of the film, going down mental avenues trying to sort out the foreshadowing clues and if this changed anything for me. The answer is no. I think it was one of the weaker elements, but led to a strengthened relationship and union between husband and wife, restoring a balance here. Both Felicity Jones and Adrien Brody are fantastic in this, but if we have to choose come Oscars night, I hope Jones gets the Supporting Actress award. Ironically, the first third of the film in which Jones isn’t present is probably the most compelling from a story perspective. I’m a history buff, and the real-life advertisement clips of Pennsylvania being the state with the most single-owner homes were cool. I’m still a holdout for A Real Pain for Best Everything at the Oscars, but there’s space for more than one Holocaust story in the cinematic 2024 world. I just hope that if this film wins, Corbet and Brody acknowledge the history and the legacy of the Holocaust that inherently comes with the story of a Holocaust survivor in a way that serves this film.

Wonderful review. A great prep before watching this movie.

No longer a Guy Pearce fan since he too is an anti semite. Sigh. But I love the leading couple.

Does your dad know about Google Translate? 😉

And I also loved learning about your family history. I’m hopeful for A Real Pain too.