Lucky Hank Review: Not all is lucky for Odenkirk and co in this Richard Russo adaptation

I'm joined by my dad, a retired professor, for this review of a professor’s life in season 1 of AMC's “Lucky Hank”

“Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated.”

― Confucius

A plot summarized, more or less.

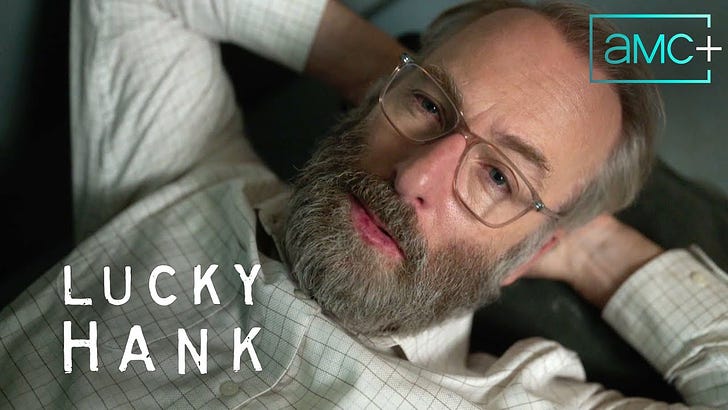

An adaptation of the novel, Straight Man, by Richard Russo (Empire Falls) and adapted for TV by Paul Lieberstein (Toby, from The Office) and Aaron Zelman, Lucky Hank (AMC) tells the story of William Henry "Hank" Devereaux, Jr (Bob Odenkirk)., a very unhappy English Department chair at an underfunded liberal arts college (fictional “Railton College”) in Pennsylvania. He is married to Lily (Mireille Enos), a high school administrator, who is considerably younger and definitely cheerier than Hank, and you sense from the get go she is getting tired of Hank’s “grumpy grandpa” acts and wants to experience a new chapter in her life, one in which she’s no longer saddled down with child rearing (her grown daughter, Julie, is married to the unfaithful and boring Russell) and handling Hank with kid gloves, and can rediscover and indulge in her own interests. Then there’s Hank’s tenured colleagues and the Railton administration who round out the show’s cast. Hank comes across as a man child in many ways - his development stunted by his own famed professor father’s leaving him and his mom at a young age,- and he can be callous when it comes to how he handles the professors around him who want to be fathered or mothered. In any way, the other professors (save Billy, an older professor who fears her job is in jeopardy because of ageism) are all pretty unlikeable and definitely narcissistic with an inflated sense of purpose about the work they are doing.

A life in academia

Like a few of the show’s actors (Deidrich Bader and Enos among them), I grew up the child of an academic. My dad spent many years as a Poly Sci professor at a mid-level liberal arts college and so listening to Hank and seeing the world of Railton College and all its dysfunction come to life for me, was almost cathartic and it definitely elicited a few “yup this tracks” laughs. I also had the pleasure of watching episodes 1 and 2 with my dad when he visited back in April. And so it was with this, that the spark for this particular post began. I knew I wanted to tell people about the show’s lead, Bob Odenkirk’s post Better Call Saul AMC TV fore, but I also knew that to review this show without my dad, now long retired from academia and living in rural-ish Pennsylvania where he taught, not unlike the locale for Railton College, would be a lost opportunity for me. I’ve felt him in so many aspects of watching this show and as we watched asynchronously after those first two episodes, I’ve wondered about his own reflections and insights on what this show gets right and what it misses.

A viral moment

Inarguably, the show’s most memorable scene occurs in the first 15 minutes of the show’s pilot, and one played in the trailer. It’s probably the best scene of the entire first season and it’s where Hank goes off on an aspiring novelist student in his English class, who prompts Hank for feedback on his story. The story is not great (there are conversations happening telepathically which make absolutely no sense in a non-sci fi story) and the student is arrogant to boot. You can see Hank resisting at all costs to give into what he really wants to say to the student and then he explodes, letting out his true, unfiltered criticism of the work.

In this iconic scene, Hank basically lays it out for the student in no uncertain terms that the college and this student are mediocre. He will never be the next Chaucer. Hank is all but canceled as one of the students records the diatribe and then voila by the next morning when Hank awakens to pings from meddlesome peers, he realizes what happened - the video was released for all to see and it’e gone viral. What is clear in this shaming down moment is Hank is unfulfilled and like the other English professors in his tenured department, he is not really fueled by nurturing excellence in his students. He just sees the job as a means to an end. The end being the paycheck. By contrast to Hank’s outward appearance, the character of Gracie, Hank’s colleague in the English dept., appears to care more about what she’s teaching and her students, but really just cares about her own image and popularity, i.e.how many kids are on the wait list for her classes, where can she get published, is she being asked to speak at an important panel, etc.

What caught me here is how insular academia is. Bob Odenkirk, in being interviewed about the show, compares the experience to being in a cage - like all these professors are in a cage with one another - all obsessing over these very narrow scholarly subjects and so the thing that comes to engage them is less about these under-appreciated fields of study and more about one-upmanship.

Also the title of the novel, Straight Man, on which the show is based, actually references that Hank is the only normal person among all the clowns he’s surrounded by. I don’t know that Hank isn’t a clown himself, but assuming he’s the “straight man” here, dad, does the show do an adequate job in painting this aspect of academia? What are some of the nuances it misses?

Dad: There is a problem with the setting that was obvious to me as a Keystone State resident. The college and the surrounding environment in the series don’t look much like my area. As Fate would have it, the episodes were shot in British Columbia, and the college buildings are part of the university of British Columbia in Vancouver, which I have actually visited twice.

Moreover, Lucky Hank seems to be showing us how small liberal arts colleges looked about twenty years ago. The political and social context at colleges has become decidedly more PC since that time, and I doubt Hank would even be hired today at the college where he teaches. In fact anyone who is as unhappy as Hank seems to be with his job would not a sensible hire, even at a very traditional college.

Pop culture facts and Hank’s bromance

Me: A few interesting pop culture facts about this show because I love this kind of trivia and know that you do too. Straight Man, the novel the show is based on, was written in the mid 90s so before the prevalence of smartphones, cancel culture, and Gen Zers. The screenwriters had to adapt the show for modern times. Lily, Hank’s wife, is not a presence in the novel. She departs at the beginning of the novel and is barely there. Of course, in the show she’s a leading character.

Russo, the author, taught literature at Southern Illinois University (SIU) where Odenkirk went for college and they were there at the same time, though Odenkirk didn’t take any of Russo’s classes. It’s neat to think that perhaps this SIU experience served as inspiration for Railton College, but more likely it was also colored by Russo’s career at Colby College, where he taught after Southern Illinois University. Also of note, you taught at Rockford College in Rockford, Illinois, 5 hours north, at the same time Russo and Odenkirk were at SIU in the early 80s. I recognize Illinois is a big state. Afterall, Odenkirk is from Naperville, Illinois, which may as well be in a different state from Carbondale (SIU’s location).

So not only, do you have the professor from a small central PA college experience, but also the Illinois connection. I also felt like there were themes in the fictional Railton College’s challenges for money that shadowed some of the conversations of my early childhood and hearing about Rockford College. There’s a constant equilibrium that needs to be established between teaching (the joy of it), funding research for your work, endowment for the school, speaking engagements, and professional ambitions. How much of this administration work is part of the day to day when you’re a professor and how are you shielded from or do you have to proactively shield yourself? Another area I’m curious to hear your thoughts on: In the show’s finale, Hank learns his dad, a retired professor of Literature at Columbia, was asked to leave because he fabricated a story in which he claimed he was at Selma march in 1965 so he would get to do a speaking engagement and panel. Hank notes that they were living in Colorado at the time so this couldn’t be true. Both Hank’s dad and mom see no issue with this lie and for Hank it’s the catalyst that prompts him to resign as professor and run away to NYC to find Lily, who no longer wants him, we think.

Dad: I couldn’t imagine at any college where I taught being asked to leave for falsely claiming to have attended a politically progressive event. I did not have my contract at Case Western Reserve renewed in 1971, I suspect partly, because I proclaimed too loudly that I had voted for Richard Nixon in 1968. But if I had announced that I went on a Freedom Ride and really didn’t, no administrator would have likely fired me for that “fib.” If, on the other hand, I were teaching at Columbia as a famous author and told a lie that might bring embarrassment to my employers, I could at least imagine being eased out for that reason. Anyhow I found the story about why Hank’s father was let go to be mildly amusing.

Me: One of my favorite subplots in this show was the friendship between Hank and Tony, the divorced Philosophy professor, played by Diedrich Bader, who is really kind to Hank, even though I think Hank does little to earn it, apart from occasionally listening to him and playing racquetball together. In season 1, episode 6, “The Arrival” when Hank and Tony go to an academic conference where Tony asks Hank to come and watch his presentation, Hank doesn’t show up for him and can’t bring himself to say “sorry” to him. That said, Tony seems to get Hank and be OK with his idiosyncrasies, perhaps in academia, this is par for the course and Tony is lonely. I did enjoy watching these two take down the college’s President, Dickie Pope (Kyle MacLachlan), this season’s villain, who was actively cutting the faculty and almost got away with it, in a bid to gain favor for an MIT position and leave the school. Did Tony leave an impression on you? What are some your favorite subplots?

Dad: I found the first episode, showing Hank’s reaction to his students entirely believable and also quite amusing. Most of the young adults Hank encounters don’t show much interest in what he is teaching or else seem to have an unjustifiably high opinion of their meager writing abilities. Hank is obviously burnt out, and his attractive, spirited wife Lily understandably loses her attraction to her tiresome, perpetually disgruntled husband. By the end of the series Lily goes off to an administrative post in NYC, where (we are led to infer) some extramarital adventure will be taking place. I almost felt by then that it would be hard to blame poor Lily. I also enjoyed the episode about the troubled relationship between Hank’s daughter Julie and her unfaithful nebbish husband Russell. Still, I was left wondering why this sweet girl ever married such a bumbling loser.

Me: I don’t think there’s an extramarital adventure for Lily on the horizon, based on how she responded to her ex, during the posh NYC private school interview. I think being in NYC opened up for her the possibilities of fully digging into all of her interests - going to cafes, working, playing the keyboard. Her description to her realtor of what a dream day looks like for her underscores that vision. In her narration there is no Hank and no Julie.

You mentioned to me that the series captures quite well the atmosphere of the second-string “good colleges” in Eastern and Central PA, which don’t quite reach the prestige level of Swarthmore, Haverford, or Bryn Mawr and that Hank never quite achieved the scholarly potential of professors at these top tier school and fell victim to the fate of what I’m coining here as “tenure bloat” - ones who gave up on some of their professional goals once they achieved the much desired tenure = job security. You noted that Hank never completed his second novel, a fact that his onetime classmate (and a renowned novelist) inevitably brings into their conversation. Is it entirely fair to generalize about Hank in this way or does his backstory with his father, being abandoned by him, and not living up to the stature of his father’s esteemed career, also responsible for Hank’s impotence? Also note that Hank has trouble peeing, and while this may not be a literal nod to his stasis, I think it’s symbolic of this inertia.

Dad: Yes, I think Hank personifies a type that one found in the day at liberal arts colleges that served as “hedges for the Ivies.” These were or are colleges that carry some prestige but fall in ranking below the most respected of the Ivy League universities and other institutions with similar distinction. These schools typically featured professors who never quite brought out a second book or second novel but who lived off some past evanescent fame, which was often exaggerated or even manufactured. Hank is a particularly peevish, sullen exemplification of this once common professorial type. By the way, I didn’t like Hank. I have known too many people like him.

Beth: Hank is definitely hard to sympathize with, though I found that I could. Knowing some of the backstory with his relationship with his own father made me somewhat more partial to why he would act the way he does. Plus, how he engages with his own daughter, when she’s in a bad place, and he tells it to her straight, that her husband is cheating, shows compassion and kindness. He is direct and honest with her. He doesn’t avoid her because it’s not a comfortable situation or lean into his non-confrontational ways. By contrast, he shows up for her after, comes to her home and makes her tea and refrains from talking. A huge win for him, by the way. I think this illustrates how people are capable of change. And maybe that even Hank, can be. Hopefully we see a little more growth in Season 2. I hope to be able to watch this with you next season and discuss more. Thanks for making time for this, dad.